The memory that a process can access is called its address space. In all modern operating systems, each process has a separate address space and the OS enforces the separation of these address spaces so that no process can modify the memory of another process. In the Memory Management part of the course, we will learn about how the OS tracks each process' address space and enforces the separation.

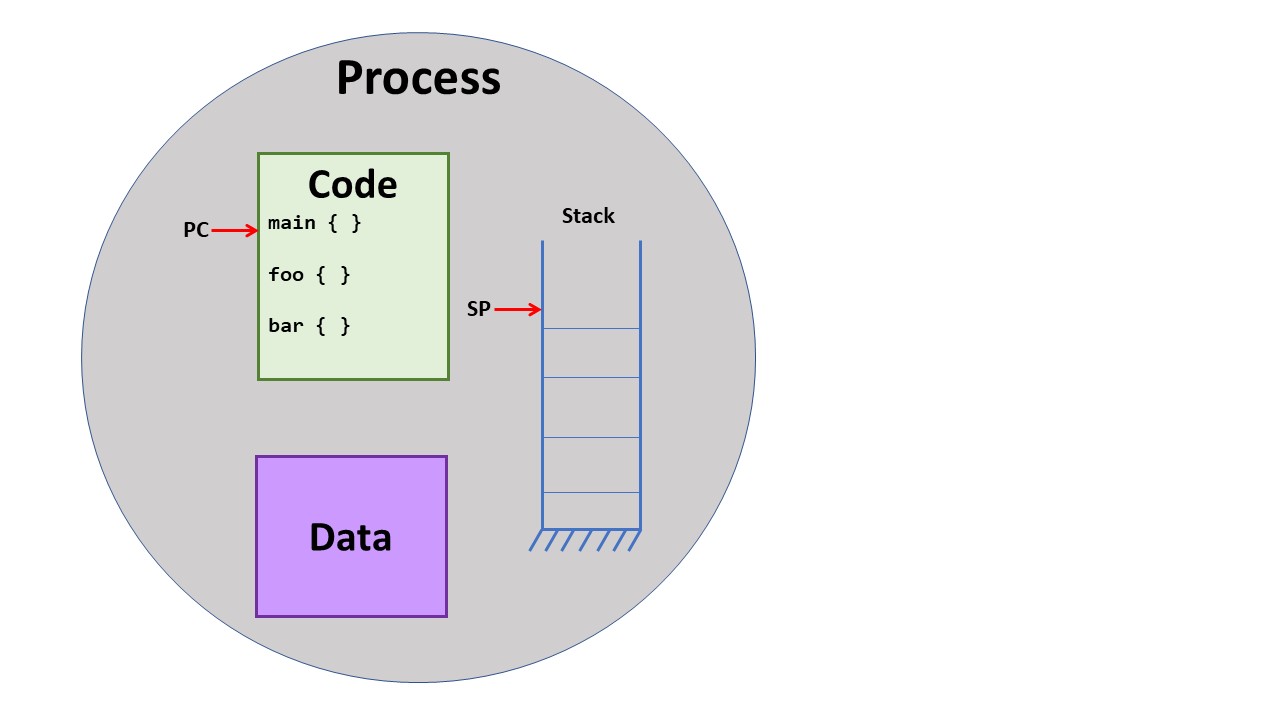

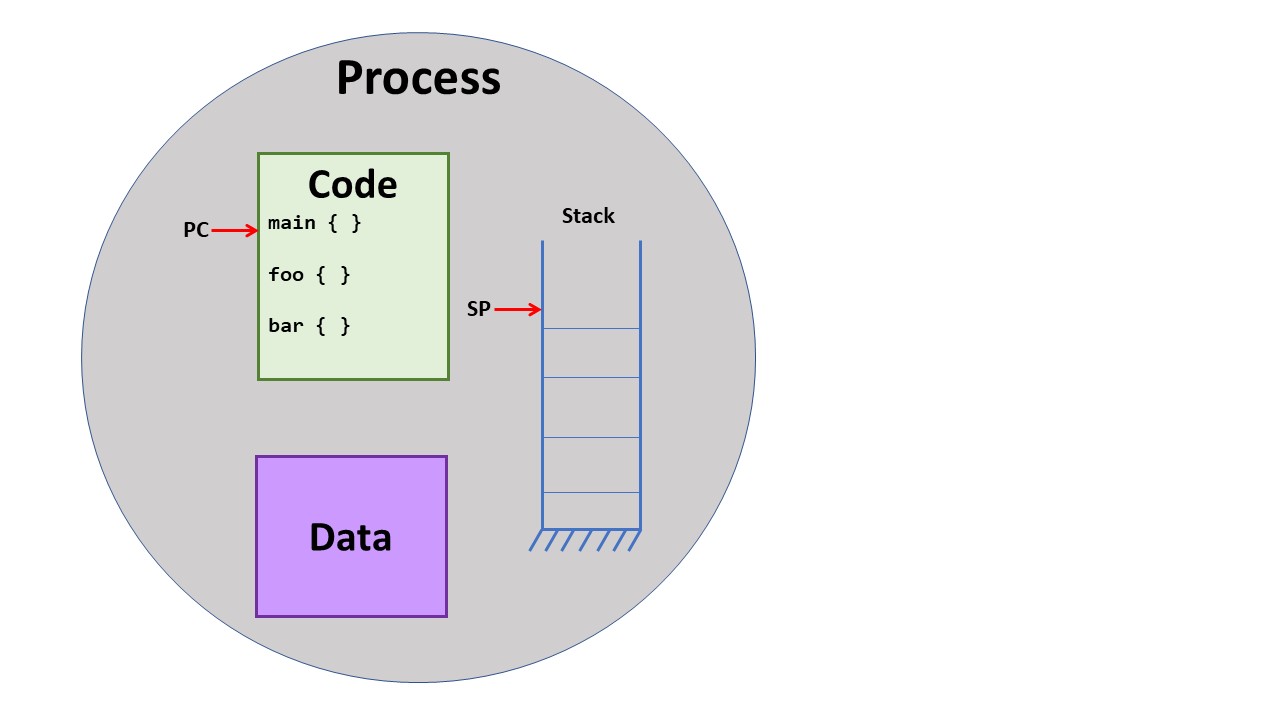

Here we can see a process with its address space (code, data, stack) and one

thread of execution, where the thread of execution is defined by the program

counter, stack pointer, and processor registers.

This is the kind of process structure that you get when creating a process

with the fork system call on Unix and the CreateProcess

system call on Windows.

Up to this point, you have probably thought about programming in a strictly sequential, independent way, just like shown in the figure above. That is, each program that you have run (i.e, each process) is separate from anything else running on the computer, and the program executes step by step through the code. So, each program runs in its own address space with on thread of execution.

As we will study in the next lecture sections, programmers want to be able to

run multiple threads of execution that share the same data.

These multiple threads of execution might be used to allow parallel execution

based on multiple CPU cores or be used as a way to structure the program

in a natural way.

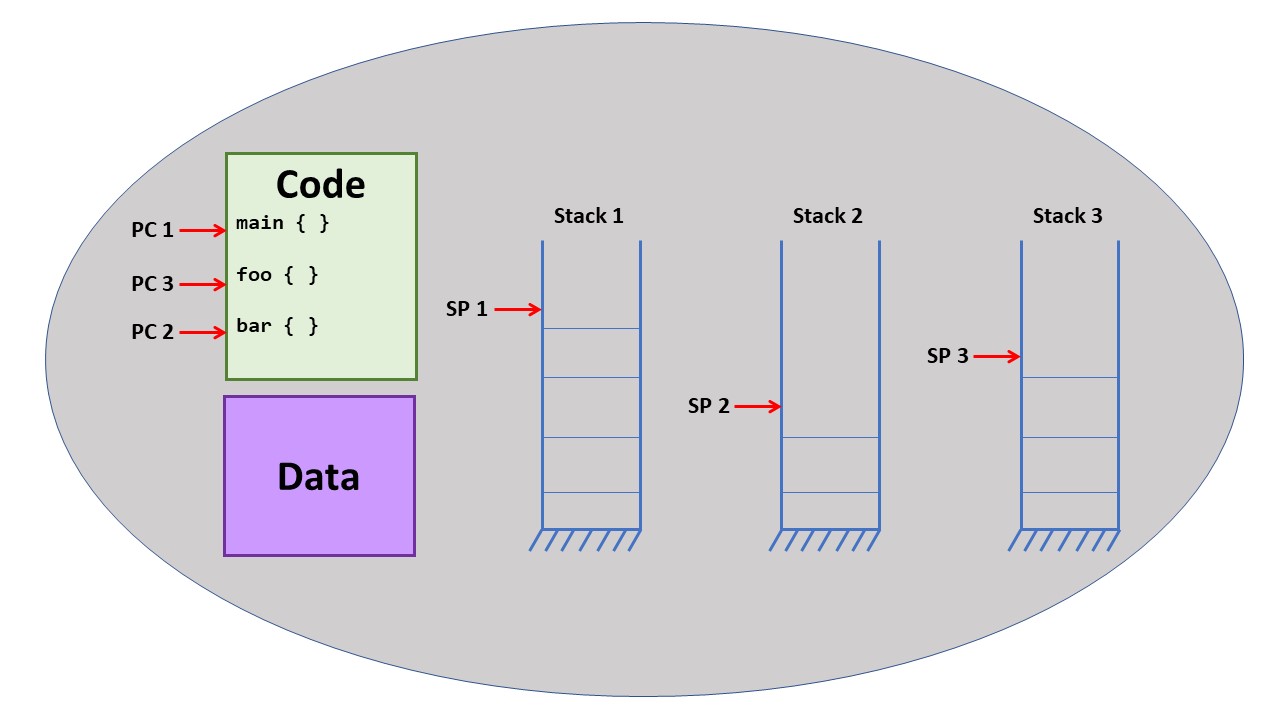

A process with multiple threads of execution might look like this:

Each thread of execution had it own stack and copy of the registers, but

shared the same code and data.

Threads vs. Lightweight Processes

We are now going to discuss the distinction between threads of execution

supported inside the operating system and those supported at user level.

This distinction can come across as subtle and confusing but is of great import.

Threads

Historically, operating systems did not allow multiple processes to share

the same address space.

There was one thread of execution per address space, like the first figure

above.

However, programmers wanted to have multiple threads of execution, so they

created a user-level abstraction, called a thread in the UNIX

world, to support this need.

Basically, they created a thread library that links with your program.

This library has some sort of create function that would be called in

the following manner:

tid = ThreadCreate(StartFunc)This function does the following:

The thread library takes care of saving and restoring registers and deciding what thread runs next. You can look at the Linux manual for setjmp and longjump to see library functions that can help you write the thread context switch code.

The operating system is unaware that there are threads running in the process. This approach to creating thread is simple and switching between threads can be very quick. These thread libraries are easy to write, so there were hundreds of different thread libraries written in the 1970's and 1980's. In fact, this was a common operating systems programming project. As a result, you can quickly design one for you own specific needs.

However, there are disadvantages to such a user-level thread library. First, consider the case where one of the threads does an operation that will cause the OS to block the function, such as reading from the terminal or waiting for a network packet. Such a read or receive operation would be a system call that would enter the OS kernel. When the OS decided that the process would block, it would be taken off the ready queue (no longer be runable). As a result, all the threads in the process would block, perhaps unnecessarily.

Second, note that even though your process has multiple threads, and perhaps is

running on a multi-core CPU, you do not get parallelism.

There is only on OS process, so only one OS-schedulable entity.

You could have a 100 threads running in your process, but only one at a time

would get to execute.

Lightweight Processes

Operating system designers knew that they need to add the ability to have

processes share the same memory, i.e., the same address space.

So, they created version of the process-create function that would keep the

same memory as the existing process, but allocate a new kernel-schedulable process

that ran in the same address space.

This means that the kernel allocated a new Process Table entry (PCB), but

pointed this process at the same memory as the existing process.

Since these processes are somewhat faster to create (because memory already

is allocated and loaded),

they were called

lightweight processes (LWP).

So, now you have multiple threads of execution in the process in the form of LWP's and the operating system is aware of each of these LWP's. So, when one LWP blocks, the others can continue. And because the OS is scheduling each LWP, they can be scheduled on separate CPU cores, resulting in true parallelism. These are important benefits.

However, similar to our discussion of threads, there are two disadvantages

when using LWPs.

First, while they are faster to create than full processes (each with its own

address space), they are still much slower than creating a user-level thread.

Second, since the LWP interface is defined by the operating system, it is fixed

and unlikely to change or adapt to a particular use-case or need.

Threads + Processes

And now, we will bring the two concepts of threads and lightweight processes together

because that represents the way that current operating systems and programming languages

actually work.

This layering of threads on top of LWPs

is important but unfortunately it is the part that is most confusing to understand.

The result of bringing these together is that you get the advantages of LWPs, in that

they are visible to the kernel and scheduled by the kernel, and the advantages

of user-level threads, in that you can easily write your own library with an

interface to match your needs.

The user typically interacts with the thread library, such as pthreads

(implemented as the Native POSIX Thread Library (NPTL) or

OpenMP, and

this library makes use of the the lightweight processes to create the threads of

execution.

Terminology

Unfortunately, as with many things in computer science, there are multiple terms

for the same concept used by different system.

In the table below, we can see a comparison of the terminology just for UNIX (including

Linux, of course) and Windows.

Most notably, what UNIX calls a "lightweight process", Windows calls a "thread";

nd what UNIX calls a "thread", Windows calls a "fiber".

| Commonly Used Terminology and Corresponding System/Library Calls | ||

|---|---|---|

| UNIX | Windows | |

| A kernel-supported process with its own address space |

Process

fork |

Process

CreateProcess |

| A kernel-supported process sharing its address space with other processes |

Lightweight Process

clone |

Thread

CreateThread |

| A user-level thread of execution in a process |

Thread

pthread_create |

Fiber

CreateFiber |