- Shopping Bag ( 0 items )

From Barnes & Noble

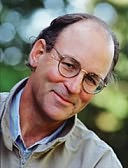

When the massacre of his people began, young Deo was a Burundian medical student. For six months, he stayed one step ahead of the Hutu militia, his life saved at one point by a kind Hutu woman who pretended that he was her son. Finally he made his way to America, but his troubles were far from over. In this book, so aptly titled, Pulitzer Prize-winning author Tracy Kidder describes Deo's hard days and long nights as an illegal immigrant in the most dangerous parts of New York; sleeping in abandoned buildings and crack houses, working at starvation wages. Though still grappling with his African nightmares, he longs to resume his education. Finally, with the help of benefactors, he is able to fulfill that ambition, eventually completing his medical studies at Dartmouth. Then he does the nearly unthinkable: He returns to his still-ravaged homeland to build a clinic. Accompanied by Kidder, he travels through the scenes of the genocide. Now in paperback. (Hand-selling tip: As one early reviewer wrote, Kidder writes with "an anthropologist's eye and a novelist's pen.")

Overview