- Shopping Bag ( 0 items )

From Barnes & Noble

The Barnes & Noble ReviewWhen a Pulitzer Prize and National Book Award winner stumbles upon a crusading Harvard physician and medical anthropologist battling TB and crushing poverty in Haiti ("the most disease-ridden country in the hemisphere"), the result is nothing short of a defining moment in publishing.

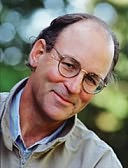

For his first foray into biography, Tracy Kidder, a master of the nonfiction narrative (Hometown, Old Friends, Among Schoolchildren, House, The Soul of a New Machine), applies his journalistic expertise and gentle storytelling skills to the life of Dr. Paul Farmer, an infectious-disease expert who's made the world's poorest and sickest his life work.

Kidder weaves a tale that is full of drama, hope, and triumph, as he accompanies the pale, skinny, disheveled doctor from the mud huts of rural Haiti and the slums of Peru to Siberia's prisons, where drug-resistant strains of TB thrive.

Writing in the first person but only occasionally interjecting himself into the story, the author recounts Farmer's unconventional childhood and describes his grueling travel schedule on behalf of his nonprofit organization, Partners in Health, and his saintly devotion to his cause.

More than a biography of Dr. Farmer, Mountains Beyond Mountains is a chilling head-on look at global public health care. Trite as it sounds, this is a book that has the power to change everyone who reads it. Sallie Brady

Overview