|

Motion Perception | Crowds and Multi-Character Perception |

| Character Behavior | Lighting | Impact of Audio |

While perceptual applications in animation heavily overlap those of film, the increased creative flexibilities of animation (color, voice, body shape, degree of realism) introduce additional challenges to comprehension and design not seen in traditional film. Here, we explore applications of perception to animation, including motion perception and character behavior. Detailed resources related to these sections can be found here.

Motion Perception

Motion perception in animation follows many of the same principles as does motion perception in film. However, since animated motions must be generated computationally to some extent, the issue of how to generate perceptually plausible motion also provides an interesting platform for experimentation. Humans can recognize motion type, character gender, and even character identity from motion capture data displayed using point light walkers, a cloud composed of a series of joint markers moving through space. Even animals can also be recognized by their motion as a PLW [11]. However, for the purposes of this discussion, we shall consider only the generation of perceptually plausible humanoid motion.

One of the most difficult challenges in synthesizing human motion is how to make it look real. Overly accurate solutions, such as full computational synthesis models can appear overly cyclic and "faked" [8]. However, discontinuities in visual motion are perceptually salient. Stability and order are also key to creating realistic motion [6]. Bodenheimer et al [2] tested the introduction of biomechanically-derived noise into cyclic computationally synthesized running motions. An introduction of about 17% noise produced the most perceptually plausible results. This result suggests that to produce truly natural motion, synthesis methods need only be "good enough": smooth enough to produce a continuous natural gait, but also containing some noisy error steps violating the perfect continuity of the motion. Further, experiments with simulation have shown that increasing the realism of the surrounding scene actually increases the viewer's visual tolerance of error in the motion [8]. Introducing a realistic context often means that more distractors are introduced into a scene. Since the human perceptual system is only capable of handling a limited number of items at a given time, these distractors force the visual system to use ensemble processing on the scene and flaws in the motion can subsequently become averaged out of the perceived motion of the scene.

One of the most difficult challenges in synthesizing human motion is how to make it look real. Overly accurate solutions, such as full computational synthesis models can appear overly cyclic and "faked" [8]. However, discontinuities in visual motion are perceptually salient. Stability and order are also key to creating realistic motion [6]. Bodenheimer et al [2] tested the introduction of biomechanically-derived noise into cyclic computationally synthesized running motions. An introduction of about 17% noise produced the most perceptually plausible results. This result suggests that to produce truly natural motion, synthesis methods need only be "good enough": smooth enough to produce a continuous natural gait, but also containing some noisy error steps violating the perfect continuity of the motion. Further, experiments with simulation have shown that increasing the realism of the surrounding scene actually increases the viewer's visual tolerance of error in the motion [8]. Introducing a realistic context often means that more distractors are introduced into a scene. Since the human perceptual system is only capable of handling a limited number of items at a given time, these distractors force the visual system to use ensemble processing on the scene and flaws in the motion can subsequently become averaged out of the perceived motion of the scene.

Accurate motions must also be oriented properly to be plausible. Experiments with PLWs imply that the direction inferred from the motion of a PLW is affected by the local motion of the points representing the feet assuming they maintain familiar positions in the display [3]. Further, the geometric model type used to represent the human affects people's ability to perceive the difference between two human motions [8]. Interestingly, however, the form of the human model does not have a significant impact on the perception of the emotion conveyed by the motion [7]. This discrepancy is likely a result of the internal representation of emotion according to the Helmholtz likelihood principle: our experiences allow us to relate to the body language expressed in the gestures of the motion, yet do not allow us to exactly generalize from one motion to another in the context of a new physical representation of character. This juxtaposition of principle does suggest that expressive motions can be generalized across character without loss of expressive power and also adapted to the parameters of the new character.

Click here for more information on motion perception in animation.

Crowds and Multi-Character Perception

Crowds and multi-character situations provide occasions where multiple characters must interact in a given scene. While character behavior can give us some guidance on how to construct perceptually plausible character interactions [2], creating general plausible character motion en masse requires a more careful consideration. Studies on the simultaneous motion of multiple objects within a scene reveal that sets of objects are visually clustered into as few sets as possible according to a variety of similar physical attributes [1]. Similar objects tend to appear to move as a set. In swarm or crowd animation, these findings can be used to prioritize the motion of an individual or set of individuals from a crowd by creating smaller subsets of moving objects whose primary perceptual attributes different distinctly from the surrounding contextual objects.

Crowds and multi-character situations provide occasions where multiple characters must interact in a given scene. While character behavior can give us some guidance on how to construct perceptually plausible character interactions [2], creating general plausible character motion en masse requires a more careful consideration. Studies on the simultaneous motion of multiple objects within a scene reveal that sets of objects are visually clustered into as few sets as possible according to a variety of similar physical attributes [1]. Similar objects tend to appear to move as a set. In swarm or crowd animation, these findings can be used to prioritize the motion of an individual or set of individuals from a crowd by creating smaller subsets of moving objects whose primary perceptual attributes different distinctly from the surrounding contextual objects.

Facial perception is distinctly different in animated crowds than in traditional film. Most importantly, by trying to perceive multiple faces simultaneously, ensemble perception must be engaged in order to be able to process so many visually complex items simultaneously [5]. Studies have shown that the human perceptual system performs equally well in perceiving the emotion of an entire crowd of people as it does for a single face. This suggests that film makers can use the overall facial expression of the crowd to quickly communicate intricate details about the overall tone of a scene.

As a result of ensemble perceptual mechanisms, however, certain key distinguishing features of individual faces in the crowd become obscured. Farzin et al [4] used Mooney faces, facial images where all primary identifying clues have been obscured, to determine that individual face recognition is possible in the periphery, though more difficult. This low-level representation and hindrance of facial recognition means that animators can shorten rendering times for crowds by simply compute low-level facial features of individuals within the crowd without sacrificing the perceived realism of the scene.

Click here for more information on the perception of crowds in animation.

Character Behavior

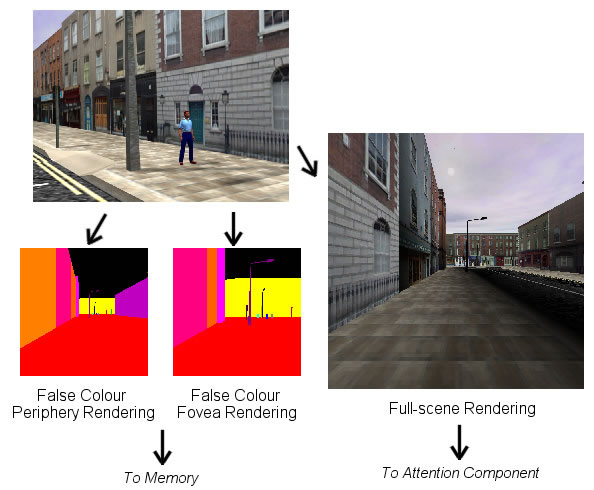

When developing accurate humanoid characters, animators must attempt to replicate the ways in which humans interact with their environment. Ironically, the way humans interact with their environment is driven by their perception of the world around them. Recent work in developing realistic virtual agents has focused on developing perceptual drivers to help the agent appropriately interact with its environment, such as appropriate attention models [3] and memory models [4]. The visible accuracy of these sorts of synthetic perception mechanisms could aid exploration into the actual working of the human perceptual system by forcing researchers to systematically replicate the workings of human perception for a virtual model.

When developing accurate humanoid characters, animators must attempt to replicate the ways in which humans interact with their environment. Ironically, the way humans interact with their environment is driven by their perception of the world around them. Recent work in developing realistic virtual agents has focused on developing perceptual drivers to help the agent appropriately interact with its environment, such as appropriate attention models [3] and memory models [4]. The visible accuracy of these sorts of synthetic perception mechanisms could aid exploration into the actual working of the human perceptual system by forcing researchers to systematically replicate the workings of human perception for a virtual model.

As part of perceiving the world around them, realistic animated characters must also be able to appropriately interact and perceive the way other agents around them are behaving. Ennis et al [1] studied how body language and audio synchronization impact the realism of conversations between animated characters. This study concluded that desynchronized gestures heavily detracted from the perceived realism of virtual conversations. Therefore, to improve the perceived reality of character interaction, body language must be consistent with the logical progression of a character's interaction with their environment.

Click here for more resources on the perception of character behavior in animation.

Lighting

While the uses of lighting in film are equally relevant in animation, the ability to arbitrarily apply lighting to an animated scene introduces new perceptual elements toward the development of animation. Studies have shown that people are not highly skilled at the perception of the direction of source light or the consistent casting of shadows in animated scenes [1]. As a result, animators can manipulate the lighting constraints to change the viewer's overall perception of elements in a scene.

One notable documented trick used for animation is the use of lighting to hide flaws in character models [2]. Different lighting and shaders can be used to create the illusion of a smooth surface in regions where polygonal simplification has been used. The most reasonable explanation for why this works is can likely be mapped to the use of lighting for depth cues [3]: lighting two continuous surfaces so that their junction (or other flawed regions) appear to be on the same plane as adjacent regions can assimilate those flaws into the correct portions of the model. Further, heavily distorted elements of a figure can be concealed by shadow as reduced contrast makes it difficult to distinguish between different regions of the object.

One notable documented trick used for animation is the use of lighting to hide flaws in character models [2]. Different lighting and shaders can be used to create the illusion of a smooth surface in regions where polygonal simplification has been used. The most reasonable explanation for why this works is can likely be mapped to the use of lighting for depth cues [3]: lighting two continuous surfaces so that their junction (or other flawed regions) appear to be on the same plane as adjacent regions can assimilate those flaws into the correct portions of the model. Further, heavily distorted elements of a figure can be concealed by shadow as reduced contrast makes it difficult to distinguish between different regions of the object.

Also, since animation is inherently a two-dimensional medium, any effects contributing to the increased dimensionality of scene in three-dimensions are critical for preserving the illusion of an extra spatial dimension. Radonjić [3] provides an overview study of the application of lighting to deriving depth cues. By properly lighting particular objects in a scene, the animator can control the perceived depth of objects in a scene and enhance the illusion of three dimensions from a two-dimensional image.

Click here for more information on the perception of lighting in animation.

Impact of Audio

Much of the impact of audio on animation parallels the findings of audio in film. While the synchronization of an audio track does impact the perception of animated scene, it likely does so in a manner reflective of live film [1]. However, animation does have the added benefit of there often being no prior expectation for the pitch of a character's voice. Therefore, manipulation of pitch and tone of a voice can influence the audience's perception of the character's personality or for gag. A clear instance of both principles in action occurred in the recent Pixar film Up, where a high-pitched voice was used as a gag for one of the antagonists, whose voice later was dropped into a seemingly more appropriate menacing tone.

Much of the impact of audio on animation parallels the findings of audio in film. While the synchronization of an audio track does impact the perception of animated scene, it likely does so in a manner reflective of live film [1]. However, animation does have the added benefit of there often being no prior expectation for the pitch of a character's voice. Therefore, manipulation of pitch and tone of a voice can influence the audience's perception of the character's personality or for gag. A clear instance of both principles in action occurred in the recent Pixar film Up, where a high-pitched voice was used as a gag for one of the antagonists, whose voice later was dropped into a seemingly more appropriate menacing tone.

In multiple character scenarios, the appropriacy of body language tends to dominate the power of audio in terms of scene realism [2]. However, scenes with heavier multi-character interaction (debates, heavy conversations, meetings) tend to rely more heavily on audio synchronization for their realism than do dominant speaker scenes. This reliance suggests that the visual system is preferential towards body language when primarily attending to single characters as the multiple physical cues can easily be remembered. However, in multi-character scenarios, instead of disentangling and trying to remember multiple body language cues on a per-character basis, audio perception allows us to track multiple character's sentiments simultaneously as typically only one cue is presented at any given time and only one cue per character must be tracked to understand the general tone of the character's interaction.

This conclusion is further supported by Reitsma and O'Sullivan's work on scenario perception [3]. This study found that audio synchronization had relatively little impact on the detection of errors in simple simulation. Since each simulation had only a single physical interaction resulting in sound and involved only a small number of simple objects, the perceptual system could easily track the visual cues in the scene and was therefore not forced to rely on audio cues to determine the accuracy of the simulation.

Click here for more resources on the perception of audio in animation.