| Narrative Perception | Scene Perception | Cuts and Montage | Motion Perception |

| Faces | Impact of Audio |

Lighting |

Hochberg's work represents pioneering efforts in the application of perception to understanding how film works. Since then, a number of advancements in psychology have helped to fill in gaps in Hochberg's original theories. Here, we discuss work on perception in cinema, ranging from cinematic techniques to the impact of casting. Detailed resources related to these sections can be found here.

Narrative Perception

The primary purpose of most films is to tell a story. The motivating question in narrative perception centers on how the viewer becomes immersed in the story. Gibson's ecological approach to perception defines the world as one populated by observers [4]. In this world, a picture is defined as a record of an observation made by an observer and thought to be worth noticing. Moving pictures, therefore, provide an even more accurate depiction of events considered worth noticing. In the ecological paradigm, the narrative of film is the element worth noting (the recorded observation). Therefore, it is the director's control over what is shown in a film that controls how the audience will perceive the narrative presented by the film.

The recorded narrative can be broken down into a series of events. Film aims to produce awareness of this train of events and their underlying causal structure [1]. Hochberg and Brooks assert that these events are depicted at three levels: low-level vision mechanisms, relational parsing, and action schemas [1]. Low-level mechanisms characterize the low-level motions of objects a scene, and are part of motion perception. However, the higher-level processes of relational parsing and generation of action schemas initiate internal mechanisms defined by Helmholtz likelihood principle. These mechanisms allow the user to anticipate future action, forming expectation of the storyline based on experiences from normal life which result in similar stimulation to that of the plot. This sense of perceived familiarity and normalcy allows the viewer to sympathize with and engross themself in the narrative; a sensation which the director can manipulate to create "twists" in the plot: a jarring of the viewer from their connection to reality to engage the viewer the story. Whether the experiential inferences derived while watching film arise from an internal mental representation of scene and event or the directed information presented in the scene remains a topic of debate among psychologists.

Key to this engagement is the concept of awareness, more specifically the direction of active attention in a scene. Attentional manipulation engages the viewer in the plot of a film. Factors such as film cutting and scene complexity can be used to engage the viewer and control the visual momentum of the scene. This engagement controls the attentional direction of the viewer, as demonstrated in multiple gaze experiments. These experiments have shown that the ways in which viewers gaze patterns shift during sequences changing views and the proportion of time spent attending to certain objects are directly related to characteristics of the presented views and the rates at which these views change [2]. Manipulating cues to control viewer's attention allows the director to control the perception and the visual priorities of elements within a scene: the director can assure that the viewer sees critical information in the scene.

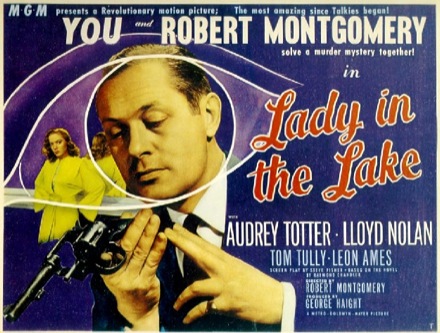

Gibson [1] proposed first-person viewership as an optimal means of attentional manipulation for the purpose of narrative engagement. In particular, these cases allow the viewer to experience the entire series of events from the eyes of the protagonist. Robert Montegomery's 1947 film The Lady in the Lake was filmed in first-person with respect to the protagonist, as Gibson suggested. However, audiences were unreceptive to the film and reportedly felt "acutely constrained as if they are placed physically in the situation of the hero for the duration of the film." The forced participation affect described by audiences suggests that part of the illusion in watching film is acting as a passive observer: the viewer maintains their own freedom of decision and emotional control instead of being placed in a scenario where they are no longer the passive observer but instead an unwilling participant unable to make choices in their surroundings.

Gibson [1] proposed first-person viewership as an optimal means of attentional manipulation for the purpose of narrative engagement. In particular, these cases allow the viewer to experience the entire series of events from the eyes of the protagonist. Robert Montegomery's 1947 film The Lady in the Lake was filmed in first-person with respect to the protagonist, as Gibson suggested. However, audiences were unreceptive to the film and reportedly felt "acutely constrained as if they are placed physically in the situation of the hero for the duration of the film." The forced participation affect described by audiences suggests that part of the illusion in watching film is acting as a passive observer: the viewer maintains their own freedom of decision and emotional control instead of being placed in a scenario where they are no longer the passive observer but instead an unwilling participant unable to make choices in their surroundings.

Click here for further information on narrative perception.

Scene Perception

Scenes for the building blocks from which the narrative of a film is constructed. Each scene contains some subset of information relevant to the plot, but the information presented within a scene is critical to how the viewer perceived both the scene and the overall film. Gestalt psychology discusses scene perception in terms of global perception. Global perception implies that some overall measure of the simplicity of a scene can be derived and applied to some overall unit. However, the definition of "some measure" and "some unit" are dependent up the content and context of a given scene [5].

Hochberg [5] proposes a more definite model of scene perception. His piecemeal perception model suggests that the windows for the perception of the scene are equivalent to those in which perceptual organization occurs (pieces of the scene). Overall perception is then accomplished by binding the attributes together using spacial cues (the whole scene). The model quickly accounts for the presence of ensemble perception in scenes [2]. Since the individual objects within the scene form the smallest perceptual units of the scene, ensemble perception can quickly summarize the low-level features of each of these objects to account for their reduced resolution in the periphery. Summarized features can include position, direction of motion, speed, and orientation. The summarized data allows viewers of film to more readily view attend to primary objects while quickly understanding the contextual information documented in the scene, even if the context is in motion.

In addition to the information content of objects in the scene, camera angle can impact the perceived depth of the scene [3]. Viewing primary attended objects from angles where the depth cues are obscured can hinder the illusion of three dimensional viewing in traditional film (such as a cube viewed along a flat face or at a corner). Furthermore, since objects at the edges of the frame tend to be more perceptually salient, using the wrong viewing angle can distort the appearance of figures at the edges of scenes. The perceptual system tends to favor symmetrical figures. As a result, the visual system has a tendency to "complete" occluded objects using their symmetrical form. Bad camera angle or cut-off of important information can make completion errors at the edge of the frame highly salient.

In addition to the information content of objects in the scene, camera angle can impact the perceived depth of the scene [3]. Viewing primary attended objects from angles where the depth cues are obscured can hinder the illusion of three dimensional viewing in traditional film (such as a cube viewed along a flat face or at a corner). Furthermore, since objects at the edges of the frame tend to be more perceptually salient, using the wrong viewing angle can distort the appearance of figures at the edges of scenes. The perceptual system tends to favor symmetrical figures. As a result, the visual system has a tendency to "complete" occluded objects using their symmetrical form. Bad camera angle or cut-off of important information can make completion errors at the edge of the frame highly salient.

Dominant colors within a scene also attribute to the overall setting. Colors are most readily identified by category, not exact shades [4]. Studies have shown that, in realistic environments like traditional film, the categorization of color is actually independent of the illumination of the scene. Color categories can then be used to visually associate different elements of the scene, like characters belonging to some particular group without forcing the viewer to recognize the individual characters. Films like Avatar also manipulate color for the purpose of wonderment: introducing foreign color paradigms jars the viewer's expectations, opening their minds to the new "reality" of the film.

Click here for more resources on scene perception.

Cuts and Montage

The perceptual system has evolved to function in the real world, where action in the environment is generally continuous. However, in cinema, as a passive observer, the camera dictates what information the viewer can take in at any given time. Cutting techniques allow the director to control what information the user sees by breaking the continuity of the film in favor of changing camera angles and, consequently, what the viewer attends to. Hochberg notes that the film makers' task is to provide the viewer with a visual answer to a question that he would normally have been about to obtain by active observation of the current event [1]. Cuts provide an interesting perceptual mechanism for such question/answer patterns as they transition the viewer both within a scene and between scenes by breaking the visual continuity of a narrative.

Understanding how the perceptual system handles cuts requires an understanding of how we process narrative. Along with the relation of information in a narrative to learned experiences (discussed in Narrative Perception), the mind forms an internal representation of what is going on the scene. According to Gibson, this representation is based on the literal information presented in each scene [5]. Alternatively, Hochberg and other modern psychologists assert that narrative is internalized using an abstract representation onto which direct visual information can be stitched into its appropriate location within the story [1, 4]. This abstract narrative model functions based on the poverty-of-the-stimulus argument: "if the output is richer than the input, then some work must have been performed by a smart cognitive module." [5] In the case of this model, the "smart cognitive module" is the perceptual system's mapping of the visual information presented by a scene to the narrative space, which takes in raw visual information and produces comprehension. Here, we will compare how the two approaches can be used to explain common cutting techniques: general cuts, establishing shots, jump cuts, flashback, and montage.

While cuts are useful for transitioning the viewer to different aspects of a scene, they do suffer from many perceptual challenges including limits on short-term visual memory [2], breaks in continuity, and visual or temporal consistency. Gibson's general view of cuts is that they are only useful should there be some "common invariant" between related cut scenes. These invariants orient the user as to the physical location of the scene within the narrative by allow the user to trace common information during the film. While he points to split-screen techniques as a potential solution to transitioning views without a common invariant, he notes that this technique can potentially introduce new perceptual challenges as it forces the user to perceive an event from multiple perspectives simultaneously. However, the internal representation theory uses the storyline to track common information across cuts. In this approach, the director can control the visual momentum of the scene. Different patterns and rates of cuts can prevent a scene from going cinematically dead -- no more interesting information is being presented in the current scene. However, cuts cause alterations in the gaze cues in the scene. In simple scenes, the glance rate is actually proportional to the cutting rate, whereas the inverse is true for overly complex scenes (complex scenes need to be processed more deeply to answer cognitive questions about the scene content). Therefore, cutting can be used to hold the viewer's attention while maintaining the tone of the piece through momentum.

Gibson's resolution to the lack of a common invariant between cuts is priming a scene using an establishing shot. An establishing shot presents the underlying contextual information of a scene in a single shot, creating an information foundation for cuts within the scene. However, the internal representation approach to narrative perception does not require the use of establishing shots. This approach implies that a cut need only fit into the overall narrative representation to be comprehended, not within an established scene context.

Jump cuts tend to be regarded as evidence of bad film technique. They are formed by the juxtaposition of two similar shots with only a slight shift in camera angle. This shift generates a jarring discontinuity in the progression of the film. In Gibson's literal information approach, this jarring occurs as it is an impossible between the information presented in the initial scene and the ensuing scene of the cut. Hochberg's abstraction model, however, relies on other perceptual mechanisms (motion perception) to explain why jump cuts fail.

Flashbacks indicate a significant discontinuity in two dimensions: spatial and temporal. In Gibson's information model, flashbacks must be made clearly intelligible and well-tied to the initial scene or otherwise disorient the user. However, more recent work has revealed that people have learned to read flashbacks remarkable well and accept increasingly subtle cues to follow them. This discovery maps to the abstract representation model, where a flashback can be seen as a foundational moment designed to explain (or foreshadow) significant elements of plot. This plot element forms a scaffold to supplement the comprehension of the flashback and anchor its place in the film.

To a lesser extreme, however, montage also relies on heavy cuts that must be related across a series of views. Gibson's information model considers montage to be based on the assumption that any juxtaposition of shots will form a unified image with new meaning. In the narrative representation model, the juxtaposition in montage instead forms a metaphor without the aid of spoken narrative and subsequent cuts break visual continuity as a mechanism to make the viewer aware of this new metaphor. The law of aesthetics defines the bounds of when montage fails: when the essence of a scene demands the simultaneous presence of two or more factors in the same action, montage is inappropriate. According to the abstract narrative model, this would cause the elements of montage to be simultaneously mapped to multiple lines in the narrative, and potentially complicated procedure violating the simplicities thought to underlie the linearity of the abstract internal representation of the narrative.

Click here for more information on cuts and montage.

Motion Perception

The basic problem in the comprehension of single shots in a film is that of perceiving the motion within the shot [12]. In the case of cinematic perception, our discussion of motion perception revolves around the way motion is used in terms of both scene perception and cutting technique.  As per the discussion on scene perception in film, a scene is comprehended at three different levels [5]. At the first of these levels, low-level sensory receptors respond to small displacements on the screen and to the differences between movements. This response functionality implies that we perceive the framework-relative paths of motions (motion local to the scene), not absolute motions (motion of the exact object). This sort of motion with respect to local stimulus is known as induced motion. Effects of induced motion can commonly be seen where a stationary foreground stimulus appears to be in motion when places against a moving background (see Demos). This type of illusory motion allows the film maker to control the pace and apparent motion of an object through as simple a change as placing an object in front of a moving backdrop (often done using a green screen, for instance, when filming someone driving a vehicle). Other elements of a scene, including elements of the background, can have tortional effects on the eye and cause a visual mislocalization of elements within space, making objects appear to be placed in the wrong parts of the scene [13].

As per the discussion on scene perception in film, a scene is comprehended at three different levels [5]. At the first of these levels, low-level sensory receptors respond to small displacements on the screen and to the differences between movements. This response functionality implies that we perceive the framework-relative paths of motions (motion local to the scene), not absolute motions (motion of the exact object). This sort of motion with respect to local stimulus is known as induced motion. Effects of induced motion can commonly be seen where a stationary foreground stimulus appears to be in motion when places against a moving background (see Demos). This type of illusory motion allows the film maker to control the pace and apparent motion of an object through as simple a change as placing an object in front of a moving backdrop (often done using a green screen, for instance, when filming someone driving a vehicle). Other elements of a scene, including elements of the background, can have tortional effects on the eye and cause a visual mislocalization of elements within space, making objects appear to be placed in the wrong parts of the scene [13].

Distance between moving objects and primary characteristics, like orientation or color, can change the perception of a particular set of motions between global (moving with respect to the scene) and local (moving with respect to other elements of the scene [1]. Global attributes are more readily perceived than local attributes, making global motions often the more desirable mechanism for conveying motion. However, the perceptual system tends to cluster elements together into the minimum number of group. These clusters are formed by elements in the scene that are proximally located and have similar sets of properties. Often the motion of elements of a cluster perceived as the generalized motion of all elements in a cluster. This aggregation and generalization of moving objects helps to explain why chase scenes tend to have the chase participants stand out so easily from the rest of the crowd: all extras are clustered together and the motion of the chase participants can be identified independently of these clusters.

The cutting and production techniques used by film makers can also have a significant impact on the perceived motion within a scene. Klopfer [6] conducted an experiment on the perception of ballet motions cut at different points: one set with preparatory then executory steps and one with executory steps followed by prepatory sets. These motion sets were shown to a group of expert dancers and lay observers. Although the experts were more tuned to spot errors in the motion, both sets of participants noted the unnaturalness of the executory-prepatory sequence. Film makers must be careful to preserve such establishing elements of motion to preserve the smoothness of motion within a film.

Click here for more information about perception of motion in film.

Faces

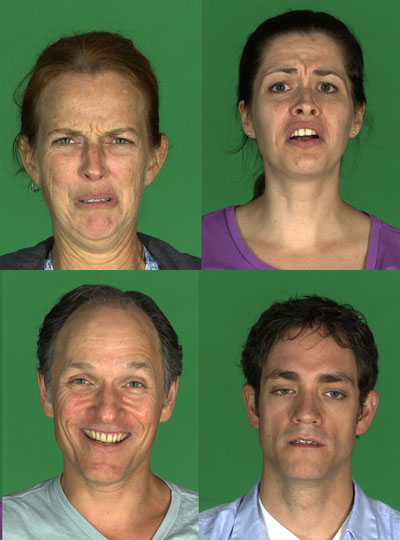

The human face is one of the most powerful mechanisms for conveying identity and emotion. From birth, the human perceptual system is tuned to recognize faces and facial expressions. However, the exact mechanisms underlying this recognition are not entirely known. In film, when character recognition is often critical for understanding plot, film makers can use facial perception to understand different lighting and concealment techniques to manipulate the audience's ability to recognize and read particular characters.

In terms of facial recognition, various studies have concluded that regions of the face containing the greatest identifying power include the hairline, facial shape, eyes, and mouth [2, 9]. Facial motion can also play a role in facial and expression identification. Face recognition is possible in the periphery, though more difficult and gender was more difficult to detect [5]. These two findings suggest that film makers could use attentional manipulation and occlusion to obscure the identity of particular characters when presenting a scene. Further, bottom-lit characters are also more difficult to recognize, likely a by-product of the concealment of key identifying features [2].

In terms of facial recognition, various studies have concluded that regions of the face containing the greatest identifying power include the hairline, facial shape, eyes, and mouth [2, 9]. Facial motion can also play a role in facial and expression identification. Face recognition is possible in the periphery, though more difficult and gender was more difficult to detect [5]. These two findings suggest that film makers could use attentional manipulation and occlusion to obscure the identity of particular characters when presenting a scene. Further, bottom-lit characters are also more difficult to recognize, likely a by-product of the concealment of key identifying features [2].

Casting may also play a significant role in how recognizable characters in film are. Studies have shown that more attractive faces (and, likewise, notably unattractive faces) are among the easiest to recognize [9]. To a further extreme, famous faces elicit non-conscious priming as they are able to trigger preexisting target face representations. This factor allows us to readily identify cameos in a film. By choosing faces that stand-out (and conversely average faces which tend to blend in), casting decisions can aid film makers in controlling how audiences perceive their action. These decisions are also reflective of the animation principle of appeal.

The perception of facial expression has important bearing on perceiving the overall emotional tone of the scene. Faces support social computation but emotions form only a subset of possible facial expressions: subtle changes in facial expression can have heavy non-verbal communicative power. Cook and Johnston [3] examined how the perceptual system represents faces internally. They discovered that the dimensionality within the facial expression space does not conform to the semantic dimensionality within human emotions. The dimensionality within expression space may instead be determined by the naturally occurring variance present within individual facial postures rather than the generalized dimensions of human emotion. The perceptual system therefore can process the emotions of a character as a result of previously known expressions, similar to the perception of different scenes in a cut along an internal representation of the narrative (see Cuts and Montage). This implies that variability in facial emotion between characters can provide an extra sense of dimensionality in that character: the presences of various emotional expressions helps the viewer to quickly identify the emotional expression of that particular character at any given time.

Whether considering the perceptual task of facial recognition or expression recognition, the principles of facial priming and facial after-effects are a notable factor. Facial after-effects reference the biasing from a particular face or expression on the perception of subsequent faces and expressions [1]. In terms of facial recognition, viewing individuals with a particular set of facial features causes the perceptual system to adapt to expect faces of that type. Webster et al [8] determined that this phenomena explains how people can become more attune to faces of a particular culture in which they are immersed: once a viewer is accomodated to a set of natural variations within a particular race, faces with a different set of natural variation simply look foreign. In terms of expression, Benton et al [1] explored the impact of facial after-effects in a viewpoint-dependent setting. This experiment revealed that, while after-effects are a prominent phenomenon in facial perception, the impact of after-effects decreases as the angle between subsequent views of the face increases. This suggests that at least some element of facial adaptation is viewpoint-dependent. As a result, it may also be possible that facial recognition can be controlled using viewpoint as well. We explore this idea in our experimental section.

Click here for more information on the perception of faces in film.

Impact of Audio

Most studies show that audio does have a significant impact on perception of a scene except for scenes where it is the only contextual indicator of some particular stimulus, such as distinguishing details of a setting. However, in these cases, visual cues still tend to dominate the perception of a scene.

Recent studies, however, have revealed situations in which audio cues can dominate the perception of film. Carter et al [3] examined the impact of synchronization and pitch on the performance and emotion of a film clip. This study found that noticeably raising the pitch of a spoken film clip reduces both the perceived quality and emotional content of the scene. An identical effect was found for audio desynchronization in the same clip set. A similar effect was found for desynchronization of audio and conversational gesture in conversational scenarios [3]. These audio can have a negative impact of the perceived quality and emotive power of film. Therefore, although audio may have no impact on the perceived content of a scene, the audience's comprehension of a film depends at least in part on proper audio synchronization.

Recent studies, however, have revealed situations in which audio cues can dominate the perception of film. Carter et al [3] examined the impact of synchronization and pitch on the performance and emotion of a film clip. This study found that noticeably raising the pitch of a spoken film clip reduces both the perceived quality and emotional content of the scene. An identical effect was found for audio desynchronization in the same clip set. A similar effect was found for desynchronization of audio and conversational gesture in conversational scenarios [3]. These audio can have a negative impact of the perceived quality and emotive power of film. Therefore, although audio may have no impact on the perceived content of a scene, the audience's comprehension of a film depends at least in part on proper audio synchronization.

Click here for more information on the perception of audio in film.

Lighting

Lighting has a number of important uses in film. In particular, it often is used to set the tone of a scene and also to characterize the setting of a particular scene. Both of these cues can be tied directly to the internal narrative representation of a film (the story provides the emotional context appropriate for the scene) and to our expectations of the scene from previous experience (see Narrative Perception).

Lighting can also be used to control the depth of given objects in a scene [3]. Lighting, especially in scenarios where the lighting of a particular object is contrasted with its flankers, can create novel depth cues, irrespective of the actual depth measures of a scene. Depth control by lighting can create the illusion of objects being in the same plane by setting such objects in identical lighting conditions. Further, lighting can be used to generate "tunnel" effects: a light at the end of a passageway can obscure the physical depth of a passageway by ambiguating their locations in visual space. Highly lit areas also create regions of high perceptual saliency, which can pre-attentively draw the attention of the viewer to particular regions or objects.

Lighting can also be used to control the depth of given objects in a scene [3]. Lighting, especially in scenarios where the lighting of a particular object is contrasted with its flankers, can create novel depth cues, irrespective of the actual depth measures of a scene. Depth control by lighting can create the illusion of objects being in the same plane by setting such objects in identical lighting conditions. Further, lighting can be used to generate "tunnel" effects: a light at the end of a passageway can obscure the physical depth of a passageway by ambiguating their locations in visual space. Highly lit areas also create regions of high perceptual saliency, which can pre-attentively draw the attention of the viewer to particular regions or objects.

Click here for more resources on the perception of lighting in film.